(from The British Esperantist, July/August 1960)

In a letter to the Listener of 1st December, 1949, Shaw advocated a phonetic 40-letter “British alphabet” and some type of pidgin English for international use. On 4th December Reto Rossetti sent him a copy of his open letter to Mr. Robert Birley, who had stated in his third Reith Lecture, that artificial languages “had no literature”. In this R.R. said:

The Listener will not publish it, thus leaving the public with nothing to go by on the question of a common language but Birley's prejudiced ignorance and your amusing naivetés.

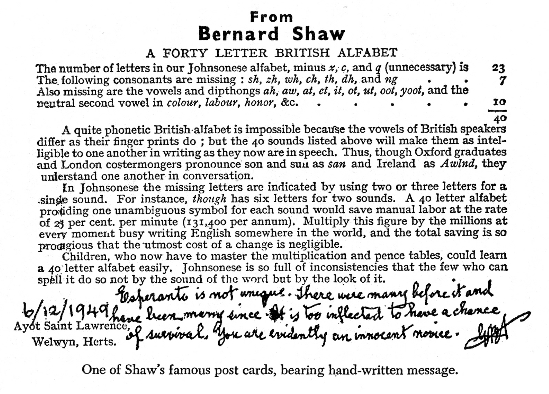

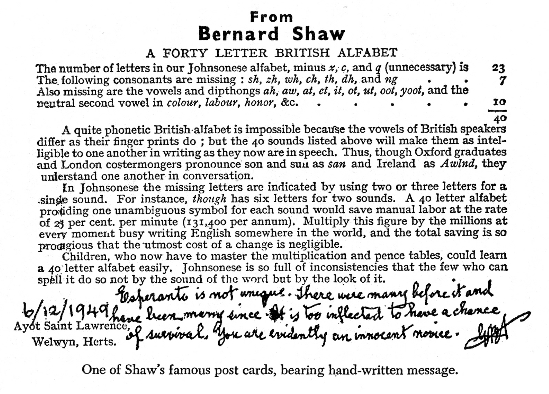

Shaw replied on the 6th with one of his printed propaganda postcards advocating his alphabet, to which he had added in his own hand:

Esperanto is not unique. There were many before it and have been many since. It is too inflected to have a chance of survival. You are evidently an innocent novice.

R.R. immediately replied pointing out the fallacies in this statement,

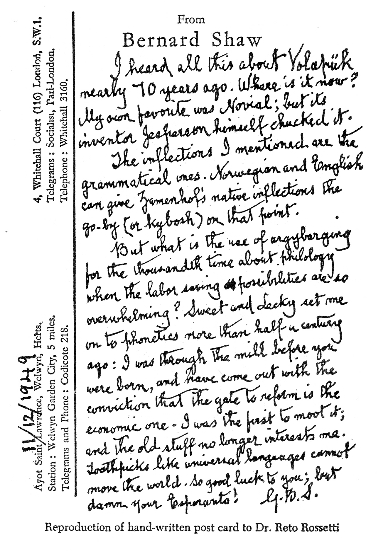

and received by return a postcard in Shaw's handwriting:

I heard all this about Volapük nearly 70 years ago. Where is it now? My own favourite (sic) was Novial; but its inventor Jesperson himself chucked it. The inflections I mentioned are the grammatical ones. Norwegian and English inflections can give Zamenhof's native inflections the go-by (or kybosh) on that point.

But what is the use of argybarging for the thousandth time about philology when the labor-saving possibilities are so overwhelming? Sweet and Lecky set me on to phonetics more than half a century ago: I was through the mill before you were born, and have come out with the conviction that the gate to reform is the economic one. I was the first to moot it; and the old stuff no longer interests me. Toothpicks like universal languages cannot move the world. So good luck to you; but damn your Esperanto! G.B.S.

To this R.R. replied inter alia:

The trouble is that people like yourself and Birley can damage Esperanto with one careless, ignorant statement, and neither I nor any other Esperantist, it seems, can get publicity to correct the harm you do. Today in Britain it seems an absolute axiom that to assess Esperanto one must not know it. If one masters Esperanto in order to judge it, one's testimony automatically becomes invalid, for then one is an “Esperantist” ... Thanks for your good luck wish. Very good luck to you too, sir, and I won't add “damn your phonetic English”, for I think it's a good thing. My own favourite language, you see, is a phonetic one.

On 20th December Shaw replied with a typewritten letter:

Past experience suggests that Esperanto, now as prosperous as Volapük was, will in a few years be where Volapük now is. But in the meantime your command of Esperanto is a very useful accomplishment, like the Morse, the A.B.C. or any other interlingual code. If it becomes a universal language through its survival as the fittest, let it. We shall see. I dislike its looks, as Chesterton did when he said that he could not bring himself to say “Tearoj, idle Tearoj, I know not what you mean”. This, of course, is nonsense; but it explains my aesthetic preference for Novial. There is nothing in all this for us to disagree about.

But why do you make your propaganda ridiculous by denouncing the views of a nonagenarian as naiveté. Beware of celebrities. I am a celebrity. Do not forget the famous retort of Ferdinand Lassalle “You are at a disadvantage, because if you call me a fool you will be certified as a lunatic, whereas if I call you a fool all Europe will believe me”. I may be a dotard; but I was not naïve in my prime; and I have been on this phonetic job for 70 years. Be as disrespectful as you like; but do not be absurd and quarrelsome.

Rossetti replied at once apologising for his phrase “amusing naivetés”, and pointing out the vital difference between Volapük and Esperanto, namely that Zamenhof gave Esperanto freedom to evolve. Three months later he wrote to Shaw again, asking permission to include a translation of Back to Methuselah, Part 1, Act 1, in the Angla Antologio. Shaw's postcard came by return:

My contracts with my publishers, present and possible in the future, do not permit of competing Esperanto editions. In any case I will not sanction excerpts: it must be the entire work or nothing. The question of whether Esperanto is a foreign language, or legally any language at all, is one for which I have neither time or taste. Cut me out of your plans: I will not discuss them further. G.B.S.

This, of course, was the end of the correspondence. Perhaps Shaw did not realise how much he was admitting in calling an Esperanto edition a “competitor”.